Blot on the Landscape – Industrial Wye Valley

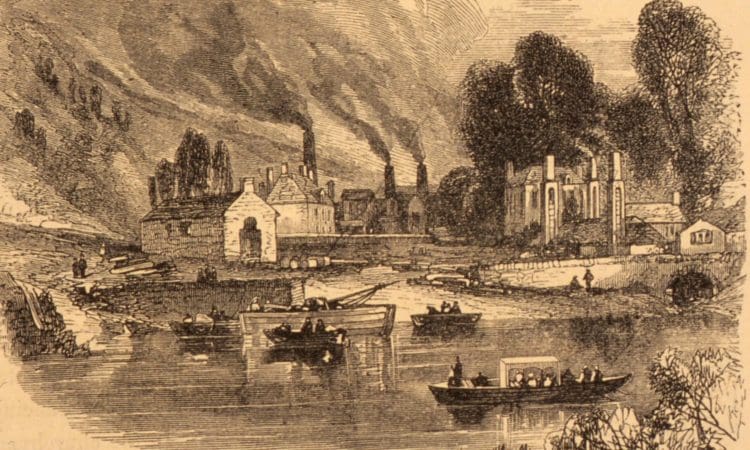

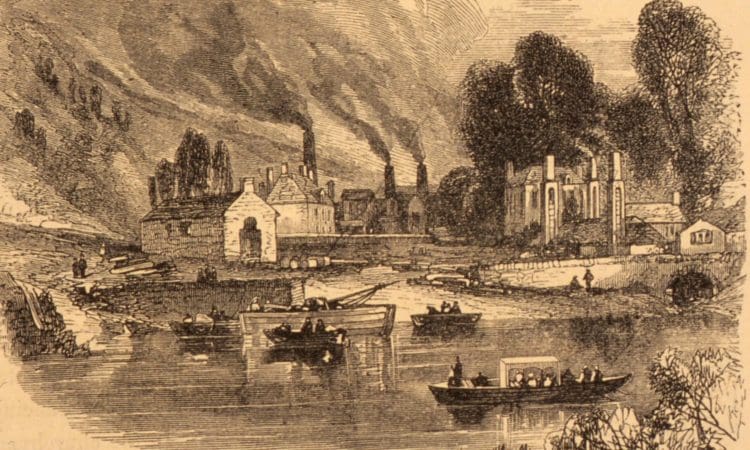

The now tranquil Wye Valley was one of the earliest areas in Britain to industrialise. Here, the raw materials needed – iron ore, water power and timber to make charcoal – were plentiful. The river provided a watery highway allowing raw materials to be shipped in and finished products shipped out with ease (at a time when roads were muddy rutted tracks). Fast flowing tributaries running into the Wye turned the waterwheels which powered the furnaces, forges, ironworks and wireworks which were at the cutting edge of Britain’s industrial development long before the Industrial Revolution. Far from being viewed as a blot on the landscape the passing Wye tourists loved the thick smoke thrown up from the iron forges which added grandeur to the scene.

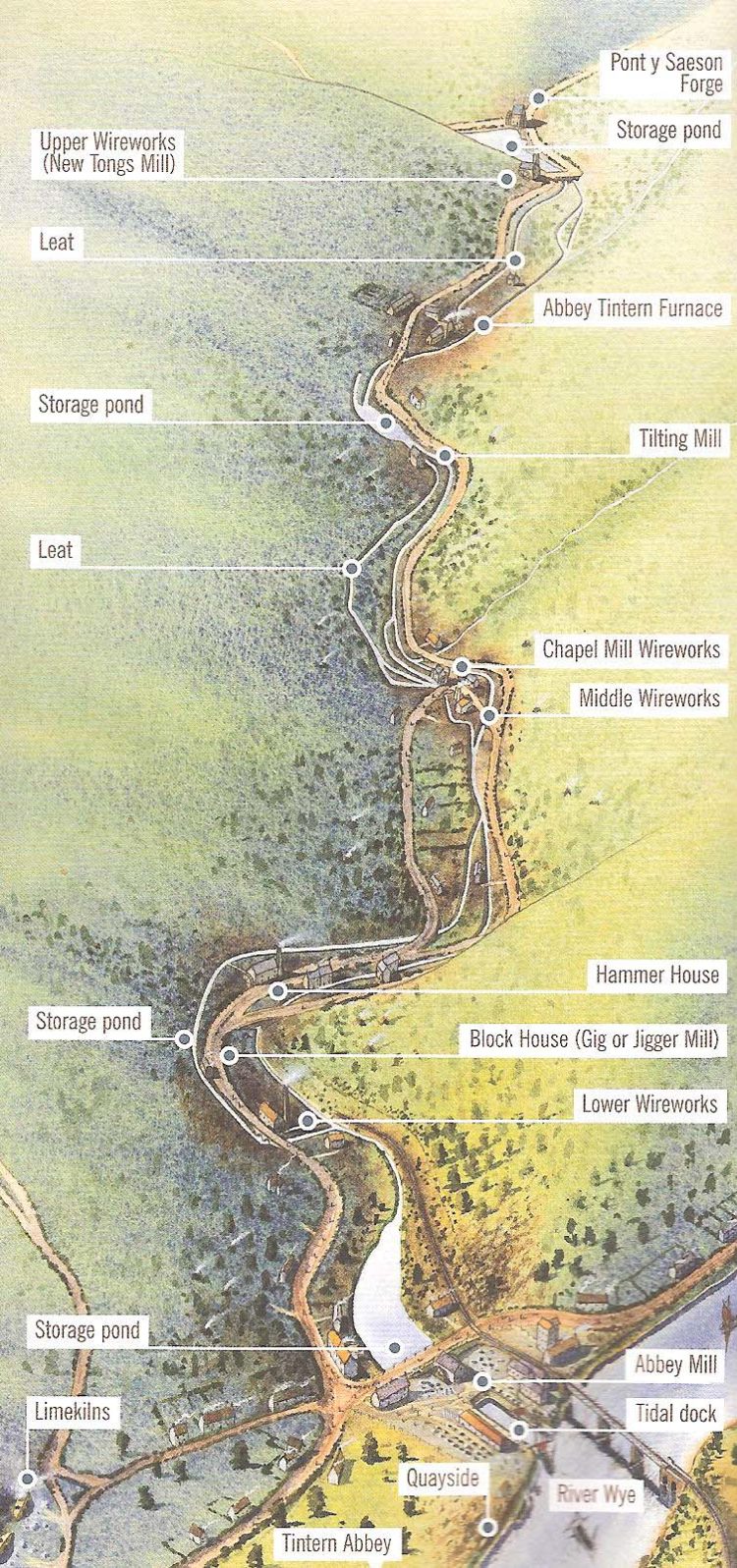

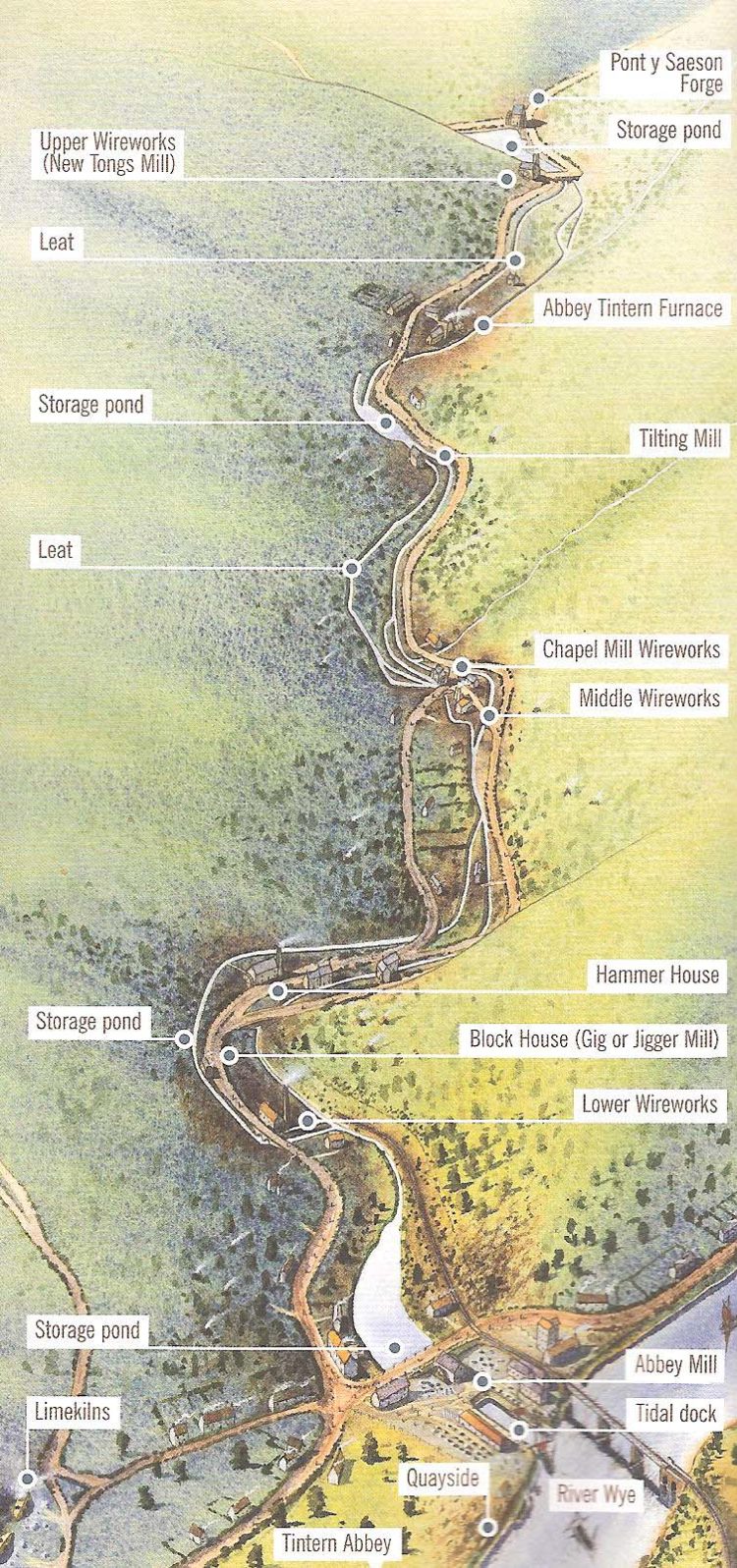

The Angidy Valley – Cradle of industry

In the 17th century, Tintern was an industrial village where hundreds of people were employed in one of the first integrated industrial complexes in the country. The village’s metal industries were at the cutting edge of industrial development in Britain for more than 300 years. Making Britain less dependent on imported goods had been government policy during Elizabeth l’s reign. The Company of Mineral and Battery Works was set up in 1566 and given a monopoly to produce wire which was a highly valuable commodity. The Company looked for suitable sites for waterwheels and found the Angidy, a gurgling brook which runs into the Wye at Tintern. Works were established here, probably on the site of what is today called the Lower Wireworks. Needing European expertise, skilled workers were brought from Germany to Tintern. Known locally as ‘strangers’, they took five years to train up local men and perfect the art of ‘wire drawing’. Before long Tintern men were drawing great lengths of wire from one inch cubes of iron.

Tintern produced some of the best wire in the country and by 1600 the wireworks were the largest industrial enterprise in Wales, employing hundreds of people. Large quantities of wire were sent to workers in Bristol who made knitting needles, fishing hooks, bird cages and buckles. Wire was also used in fashionable Elizabethan clothing, whilst thousands of people were employed making wire into carding combs for the woollen industry, wool being Britain’s main export at this time. A job at the wireworks was much sought after and wireworkers became the local elite. They enjoyed voting rights, tax concessions, sick pay and pensions which were paid to those too old to work. A priest and a school teacher were funded by the company who also supplied ale and tobacco at the annual wireworks feast.

Making wire was a skilled and time consuming activity, involving a number of different but linked processes. A constant supply of water was essential and a complex system of water engineering involving storage ponds, dams and leats was constructed. Where the Angidy flowed into the Wye at Abbey Mill a tidal dock was created to allow trows to load and unload even at low tide. This industrial activity was well established by the time the Wye Tourists flocked to Tintern. They loved the sounds of the huge forge hammers hitting metal, the thick smoke which hung over the Valley and the glow in the night sky from the furnace and forges. By the nineteenth century there were twenty or more waterwheels along the Angidy and one truly massive waterwheel stood on the river bank in Tintern, described by a visitor as having ‘the power of eighty horses’.

The wireworks continued until the 19th century. Local tradition has it that Angidy wire was used in the first transatlantic telegraph cable. By this time the industry was in decline: steam was replacing waterpower and the rushing water of the Angidy no longer held an advantage. In 1878 a new company began manufacturing tinplate but by 1895 the local newspaper was reporting that, ‘Tintern Tin Works, which have been going irregularly for some time past, closed up last Sunday with no hope of an immediate restart’. In the 20th century the site became a saw mill for stone and later timber. The only waterwheel to survive today is at Abbey Mill, whilst the most visible evidence of the Valley’s former industry is the Wireworks Bridge, built across the Wye in 1876 to link the wireworks with the railway network. Ironically by this time the works were in decline and the bridge never really fulfilled its function.

This hidden industry can still be found stretching for two miles along the banks of the Angidy which you can follow on the Angidy Trail Walk

Since Roman times Redbrook was a hive of industrial activity. First iron, then copper, and later tinplate were made here. The earliest copper smelting furnaces in Britain were established in Redbrook in 1690. A local man, John Coster, experimented with new ways of smelting copper using coal rather than charcoal. At this time Britain was dependent on expensive copper imports, so when Coster perfected the process and established a coal-fired smelter in Redbrook in 1690 he revolutionised Britain’s copper smelting industry. By 1697 it was reported that there were ships at Chepstow ‘laden with Copper-ore from Cornwall, bound for Redbrook’. Coster was now producing 80 tons of the highest quality copper, which sold for £100 a ton and was even exported to Holland.

In 1692 the English Copper Company established works in Redbrook too. Securing contracts from the Mint, they stamped out the blanks for copper coins, becoming the government’s main supplier. These were the most important copper works in the country and Redbrook soon became Britain’s copper capital. The impact on the people who lived here was profound. The copper ores were roasted to drive off sulphur and arsenic, and visitors commented that, ‘a thick yellow smoke hangs over the works which is very unwholesome as well as detrimental to vegetation’. Despite this tourists passing in 1798 thought that Redbrook was ‘the most bustling little place imaginable’ where everyone was ‘grilled in daily smoke and flame’ and ‘quiet was here wholly banished by the reverberating strokes from the iron-works’.

In the 19th and 20th centuries Redbrook became famous for its tin – the thinnest tin you could buy. The first tinplate was made here in 1774. David Tanner, a local ironmaster bought the vacant copper works and converted to tinplate manufacture in the 1790s. By 1848 Samuel Lewis wrote that, ‘Redbrook …is now celebrated for the manufacture of tin plates, of which from 400 to 500 boxes are produced weekly. In these works about 120 men are constantly employed. Tinplate from Redbrook was used to make tin cans and tin boxes. With the establishment of the Redbrook Tinplate Company the brand became famous around the world. Much of the demand came from the United States where it was used for packing tobacco. By 1949 43,500 boxes of tinplate were produced weekly and exported worldwide. The noise from the rolling mills, which operated around the clock, could be heard for miles around. Redbrook’s residents lived cheek by jowl with the sound, smell and smoke from the Works until 1961 when, unable to compete with the new Welsh strip mills, the Tinplate Works closed.

What a waste!

Centuries of metal making in Redbrook produced huge amounts of waste. Thomas Burgham, iron master at Redbrook from 1828 to 1870, calculated the waste cinders here amounted to over 500 years’ of smelting. Most waste products were recycled. Copper slag was purchased by the Turnpike Trusts to improve the roads. Slag was crushed and bought by Bristol glassmakers. The molten waste from copper-smelting was cast into copings, quoin stones and slag blocks. You can spot these dark blocks in buildings along the Wye.